The word maxim has medieval origins, I’m pretty sure.

But the phrase “Maxims for Revolutionists” comes from the tail end of a long appendix to a 1903 Bernard Shaw play, Man and Superman. The play—described as “a comedy and a philosophy”—deals with a bunch of complicated ideas about politics, marriage, gender roles, education, and social class. The appendix is presented as a book written by the fiery young character, Jack Tanner. Tanner’s work,The Revolutionists Handbook, ends with a list of 179 pithy sayings: the Maxims.

Maxim #36 will likely ring a bell. It reads, “He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.”

That saying has morphed over the years into “Those who can, do…those who can’t, teach,” and I guarantee that every educator you know cringes when they hear it. As much as I’d like to say that Shaw meant something more complex or more subtle, he definitely liked to provoke people, and I think he meant what he said.

And he went even further when it comes to higher education. This is Maxim #32:

A fool’s brain digests philosophy into folly, science into superstition, and art into pedantry. Hence University education.

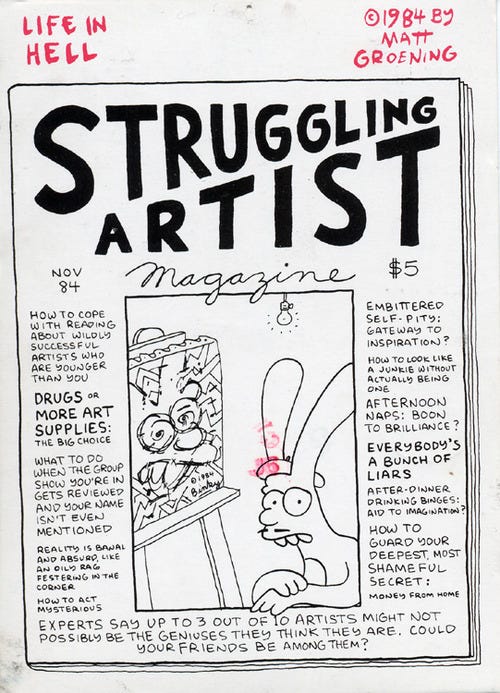

Now, I’m no expert on Shaw, and his politics were definitely complicated (big supporter of Stalin, for instance), but what I see in these phrases is the tension between making art and making money. Whether they are plays or paintings, works of art don’t always pay the bills. The trope of the starving artist didn’t come from nowhere.

Image: Matt Groening, Struggling Artist Magazine, 1984

Like many artists, Shaw’s project was to challenge his audiences, to make them consider deep political and philosophical questions in the context of entertainment. That’s how I came to see my teaching.

When I first started out, I thought I needed to have all the answers. I was worried about accuracy and truth. As I became a more confident educator, I realized that my job was actually different. My product should be in the process. My methods should help students access information and experiences, to guide them in considering difficult questions, to empower them as citizens and learners. I was not interested in offering some litany of facts that someone else had deemed the “truth.”

In other words, I made teaching into my own version of performance art. There was no line between what I did and what I made—writing, learning, teaching, even organizing were all intertwined. I admit that when I first read Maxim #32, I bristled and got defensive, but then I realized it wasn’t about me.

No, the real fools who are turning philosophy into folly, art into pedantry, and science into superstition are the corporate-minded administrators who have never DONE but somehow feel empowered to TEACH.

Let me give an example. Few people outside (or even inside) academia know what a Provost does. Technically, they are the Chief Academic Officer of a University, a position that ideally should be occupied by someone with many years of teaching experience. Universities used to (and sometimes still do) promote teaching faculty into such roles, which made for Provosts who could both DO and TEACH, and who had a deep understanding of the university as more than a degree factory. Nowadays, though, it’s possible to earn a whole degree in Provosting, which is not unlike a degree in Business Management. From what I gather, the content of such a degree includes how to move players around the chessboard of the university (aka allocate resources). But it generally does not include a great deal of classroom teaching experience. With this magical Provosting degree in hand, one can be hired into a high-paying position (like, 200-300K/year) with a tremendous amount of power over curricular and institutional decisions. This is precisely what happened to me when a newly hired Provost decided to cut the art history “program” based purely on numerical data that made zero sense in terms of the teaching/doing that I had dedicated my life to.

Maxim #38 touches on this idea about the connection between doing and knowing. It reads:

Activity is the only road to knowledge.

And this one pairs nicely with Aristotle’s take on the topic. He said:

Those who know, do. Those who understand, teach.

Now we’re getting somewhere: to really KNOW, you have to DO, and to TEACH, you have to DO, KNOW, and UNDERSTAND.

The fact that American colleges and universities are continuing to grow a class of administrators who are NOT educators is contributing to the death of the humanities, as well as the destruction of the university itself. The corporatization of American higher education is stripping away all the art, all the humanities, all the provocation, leaving only the pedantry. Students are being funneled into “career-aligned” majors without being inspired, without being challenged, without being empowered to think on their own. The arts and the humanities tend to be abstract, and not so lucrative, but they matter if we want to encourage students to be fully empowered citizens of this world.

I’ve decided to adopt my own maxim, which I took from a phrase in the introduction to Bill Readings’ wonderful book, The University in Ruins (1996). It reads:

…teaching is a question of justice not a search for truth.

With that in mind, I plan to keep DOING in whatever way I can, making justice as a form of artistic practice. I still don’t know if that looks like teaching or something else, and I’m still worried that none of this will feed the kids, but one thing I know for certain is that both the teaching and the making are vital for me. And the truth is never as simple as it appears.