Making Tracks

When I began this blog, I had recently been laid off from a position as a tenured Full Professor, and I started my story from the middle. Now, I want to rewind it back to the beginning. Don’t panic: we don’t have to go all the way back—just far enough to explain the current mishegoss. Professoring involves a lot of writing, and this space has been a great outlet—it helps me to answer everyone’s questions in “one swell foop,” as my parents used to say. Thanks for following along, and here’s hoping my thoughts can pull back the curtain a little to reveal the hidden mechanisms that power academic institutions.

So, each time I tell someone about being laid off, I hear a similar refrain: “Doesn’t tenure mean job security? How can they do that??” or “What? I thought you had a union??” Academic colleagues tend to be a bit more panicked about the whole situation, but everyone is surprised and confused. Lots of people ask about my severance package ($0), or they want to know why having a union didn’t help. They want to make sense out of something that is—quite frankly—pretty hard to explain, let alone justify. Here’s what I can offer by way of an answer…

First, let me say that OF COURSE, getting laid off is traumatic for anyone! In many ways, I’m no different from any other worker, and I’m extremely privileged and truly grateful to be safe, healthy, and relatively stable. I have the chance to get back on track in a way that works for me and my family—a HUGE advantage. Still, I worked for years to earn a job (allegedly) “for life”—I dedicated all of my professional focus to WPU, even when it didn’t love me back, because I knew I had to sacrifice to be a professor. It was what I wanted. And my hard work paid off—I earned it—a tenured position with a union contract to boot. In the end, neither of those guardrails were enough to keep me on track.

In academic speak, a “tenure track” job is a position (also known as a “faculty line”) that offers the promise of permanence, if you play your cards right. Such openings have been getting scarcer for decades, and there are also important and legitimate critiques of the tenure system, particularly with regard to equity and inclusion. The tenure process is like a kind of initiation, rife with hazing practices, and the resulting power hierarchies are very real and can be deeply harmful. Many people contort themselves into shapes they believe will please the powers-that-be in the hopes of achieving tenure; so-called junior faculty overcommit themselves to service work, carrying a huge amount of unpaid labor, and they often resist speaking their minds in an effort to achieve that gold star. And don’t even get me started on the tenured or tenure-track (TT) vs. contingent or non-tenure-track (NTT) faculty dynamics—we have a long way to go with regard to inclusion and equity among higher ed faculty and teaching staff. (That’s where unions come in, IMO.) The reality is that all university faculty jobs involve teaching, publishing your research and presenting at conferences, and serving on committees. The only difference between the tenure “track” and other jobs is that promise of security. And the respect and endorsement of colleagues in the field.

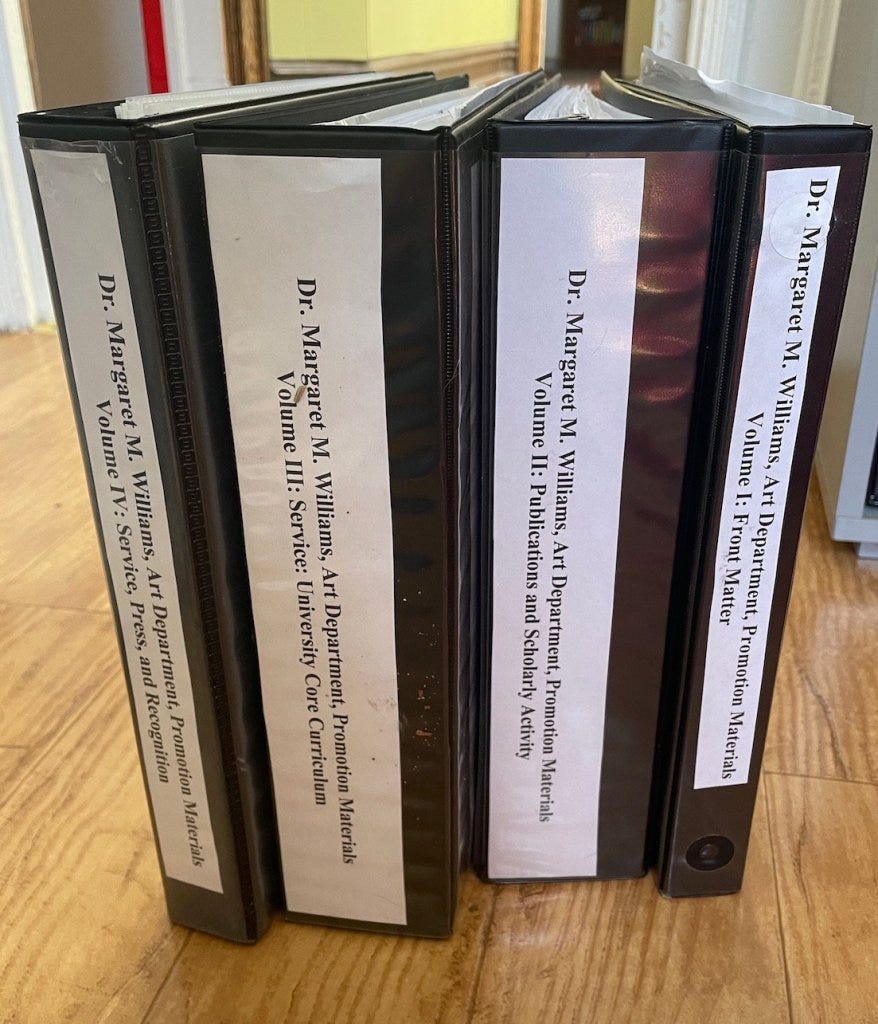

Earning tenure takes years and an incredible amount of work. My own track was relatively short (5 years) and pretty straightforward because there were clear policies and procedures laid out in the union contract. Each year, in addition to doing my regular job, I had to put together a set of binders that displayed all of that year’s achievements.

It was sort of like re-applying for my job every spring, and each time, my colleagues were engaging in substantive peer review of my work. They were confirming that my teaching and scholarship met their professional standards; they were endorsing my expertise and my value to the institution.

The WPU administration also approved of my performance, both as an individual and as a member of the Art Department, which boasted consistently high rates of enrollment and retention. We were doing a great job, and I had many meaningful roles in the department and across the university. I was becoming committed to WPU as it was committing itself to me. In fact, the tenure letter I received from the Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs specifically described “the commitment of the University” to my “continued growth and development” as a member of the faculty and the academic community. The whole thing was sooo much about academic stuff (as opposed to terms and conditions of employment) that I didn’t even have to do any paperwork with HR.

Long story short, I’m proud of the hard work I did to achieve tenure, and I still believe it’s an important academic tradition, despite its flaws. When properly respected, tenure protects faculty from being fired without cause; that’s vital because it means they are free to research, publish on, and speak about topics and issues that might be controversial. It’s not entirely about a steady paycheck, but for many intellectual and creative workers, that paycheck can mean stability and the freedom to practice a craft. (Think of a jazz musician who pays the bills by teaching—and if you’re thinking the world doesn’t need more jazz musicians, I sure hope this blog makes you think twice!)

So, why didn’t my tenured status save me? And what about the union? Outside academia, you hear that both tenure and unions make it hard to fire teachers, so what gives? How did WPU manage to get rid of a tenured union member who never even had a single student complaint in nearly 15 years?

Here’s the short version: faculty are tenured in a “department, program, or specialization,” and those terms are defined by the administration. Managerial prerogative, and a clause in the union contract, allows them to terminate a “program” like art history, and to lay off faculty affiliated with that “program.” And I was the last person hired in that “program.”

So, never mind the fact I was hired into the Art Department, and the art history “program” (i.e. major) didn’t even exist—it was approved in my second year. Never mind the fact that the vast majority of my students were either Fine Arts majors (not Art History), or General Education students. And never mind the fact that my salary was paid by the university and my direct supervisor was the head of the Art Department (not the art history “program”). The union wasn’t willing to make those arguments on my behalf because their primary concern was to “protect the contract.” A contract with a clause that gives almost all the power to the administration. Many of my colleagues believed that I was personally targeted, but the reality is that I was low-hanging fruit.

Now, here I am, six months later, still healing from the trauma, still processing what I want to do next. No matter what that next thing ends up being, I’m pretty clearly heading off the main track. We’ll see which branch line I travel next.